Read time: 8 mins

Based on Borrowing to compete or survive a pandemic? New directions in Australian fiscal federalism by Tracy Fenwick, published June 2023.

ANU research shows that subnational debt has surged to record highs in the years following the pandemic. While this debt is fiscally sustainable, it exposes structural limitations that delay states and territories’ ability to respond swiftly to crises.

Read time: 8 mins

Based on Borrowing to compete or survive a pandemic? New directions in Australian fiscal federalism by Tracy Fenwick, published June 2023.

1

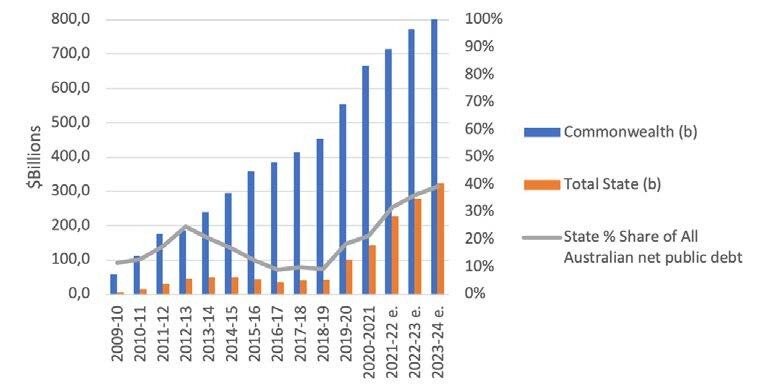

Between 2011 and 2022, Australia recorded the largest subnational debt growth in its federal history. ANU experts have analysed this rise to understand its causes and implications.

2

With no legal borrowing caps and limited revenue-raising powers under Australia’s fiscal federalism, states and territories had to borrow substantial amounts of cash to respond to the economic impacts of the pandemic.

3

Despite a record debt, Australia’s fiscal position remains sustainable, with capacity for additional state borrowing. As the need to invest in climate change and disaster preparedness grows, public aversion to debt accumulation could decrease.

The economic impacts of the 2019 bushfires, the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2022 floods have forced state and territory governments to borrow money at record levels.

Compared to 2011-12 figures, states borrowed 661 per cent more in the period of 2020-2022. This rise in public sector debt almost triples the Commonwealth’s increase over the same period (236 per cent.)

ANU experts have revealed these figures represent the highest public debt accumulation in the history of Australian federalism – higher than that experienced after the Global Financial Crisis.

But is this a short-term, pandemic-created problem – or does it expose deeper fault lines at the heart of Australia’s fiscal system?

ANU research has examined the history of Australian federalism alongside economic and political data. The findings suggest that the debt problem may be somewhat structural to the system.

ANU experts suggest three key drivers contributed to the unprecedented debt surge:

According to the researchers, these federal, in-built conditions limit the capacity of states and territories to respond quickly in times of crisis.

If unmanaged, subnational public debt can represent a risk to states and territories’ economic stability.

But ANU experts showed state-level public sector debt in Australia is fiscally sustainable, even at historically high levels: both debt interest payments and the ratio of state public debt to Gross State Product (GSP) remain low.

When compared to less centralised federations such as Canada, Australia’s subnational debt accumulation is not perceived as high by the experts, suggesting states and territories can carry more debt in the future.

However, the debt is territorially uneven. In 2022, the Northern Territory had the highest ratio of state net debt (20.4 per cent) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) the lowest (-3.8 per cent).

Variations in state wealth and the uneven impact of the pandemic have contributed to these disparities. While horizontal fiscal equalisation is designed to correct such imbalances, its three-year lag meant that financial compensation for the COVID-19 impacts did not arrive until 2022 or later.

With no legal caps on borrowing, as long as credit ratings remain high, states and territories face only one constraint: political tolerance.

Historically, that tolerance has been low. Governments perceived by the public to have overspent have often been punished at the polls.

But this dynamic could be gradually shifting.

During the pandemic, premiers were under pressure to spend more on infrastructure investment – an economic stimulus measure typically used to fight recessions.

Recent state elections suggest voters are more accepting of borrowing when it’s tied to critical infrastructure projects, rather than borrowing to fund more public services.

For instance, premiers who invested heavily in critical infrastructure, such as Mark McGowan in Western Australia and Daniel Andrews in Victoria, were perceived as good crisis managers and rewarded electorally.

According to ANU experts, this pattern could create an electoral incentive to borrow during future crises.

If Australians increasingly view infrastructure – particularly related to disaster preparedness and recovery – as a long-term, intergenerational asset, the political appetite for borrowing will likely grow.

This could mark a new direction for Australia’s fiscal federalism, where subnational debt accumulation becomes more than a short-term crisis measure.

Top image: Kym McLeod/Stock.adobe.com

“Voters are more accepting of borrowing when it's tied to critical infrastructure projects.”