Is migration going up, or down – and who should I believe?

Misleading claims of uncontrolled mass migration in Australia results from mixing Permanent and Long-Term movements with true migration numbers.

Read time: 5 mins

Based on What’s the difference between NOM and Net PLT? by Alan Gamlen and Peter McDonald, The ANU Migration Hub

Around Australia, claims are mounting that mass immigration is out of control. This is a false alarm.

Much of it relies on one dataset that is being widely misused: Permanent and Long-Term (PLT) movements, collected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

The ABS has issued multiple clear warnings that this data should not be used to measure migration. Yet a few rogue public commentators continue to do so.

The result is highly misleading claims that distort public understanding, inflame debate and undermine policy.

For example, false claims based on this misused data were used to encourage participation in a series of immigration marches this year which prominently featured self-described neo-Nazis and white supremacists.

The Australian Statistician, Head of the Australian Bureau of Statistics has characterised the misuse of PLT data to support claims of mass migration as “flat-out contradicted by the statistical evidence”.

He called this an “egregious misrepresentation” of its data and said the agency “stands ready to respond” to such misuse.

What is migration – and how do we measure it?

Migration – in the international standard sense – is when a person changes their country of usual residence. The United Nations’ definition (1998) captures this by asking: did someone live in Country A for at least a year, then live in Country B for at least a year?

This is the basis of Australia’s definition of Overseas Migration, which measures where a person has lived for at least 12 months within a 16-month window. And this in turn is the basis of Net Overseas Migration (NOM).

NOM is the figure used to update Australia’s Estimated Resident Population (ERP) – the number that governments use for funding, infrastructure planning, and representation.

This makes NOM the correct benchmark for questions about migration, housing, labour, population change and so on.

What is PLT – and why it isn’t migration?

PLT data is fundamentally different. It counts ‘trips’, which is a completely different concept from migration.

Each PLT arrival or departure captures one leg of a two-leg trip by a person who stays (or leaves) for at least 12 months. Each PLT leg, or ‘category of movement’ is classified by the traveller’s legal status, their direction of travel, and their total trip duration.

This is totally different from overseas migration. As a result, the PLT data capture all sorts of travellers and movements who are not migrants or migrations in any way, shape or form.

For example, in the PLT data people can be counted as long-term residents leaving or returning even if they weren’t living in Australia beforehand or don’t stay after arrival.

Likewise, travellers may be labelled as long-term visitors arriving or departing even when they actually live in Australia and are only taking short trips.

Even permanent arrivals can be overstated when permanent residents returning from their first brief overseas trip are counted as new migrants, regardless of whether they remain in Australia afterward.

Take a concrete example: John is a temporary visa holder who arrives in Australia to study or work. He takes five short trips outside Australia while residing here. His residency status prior to each return is not checked. And each time he returns, he declares an intention to stay in Australia for more than a year.

In the PLT data, John will account for five Long Term Visitor Arrivals. Depending on the exact circumstances, the same thing can happen with John’s departures. And it is crucial to recognise that, as long as the actual durations of each of John’s trips match his actual intentions, this is not even wrong: it is just because PLT data counts something fundamentally different from migration.

Bottom line: If you use PLT to equate with migration, you are mixing tourism, travel behaviour, temporary visa dynamics – and residence transitions –all into one confused number.

How big is the mismatch?

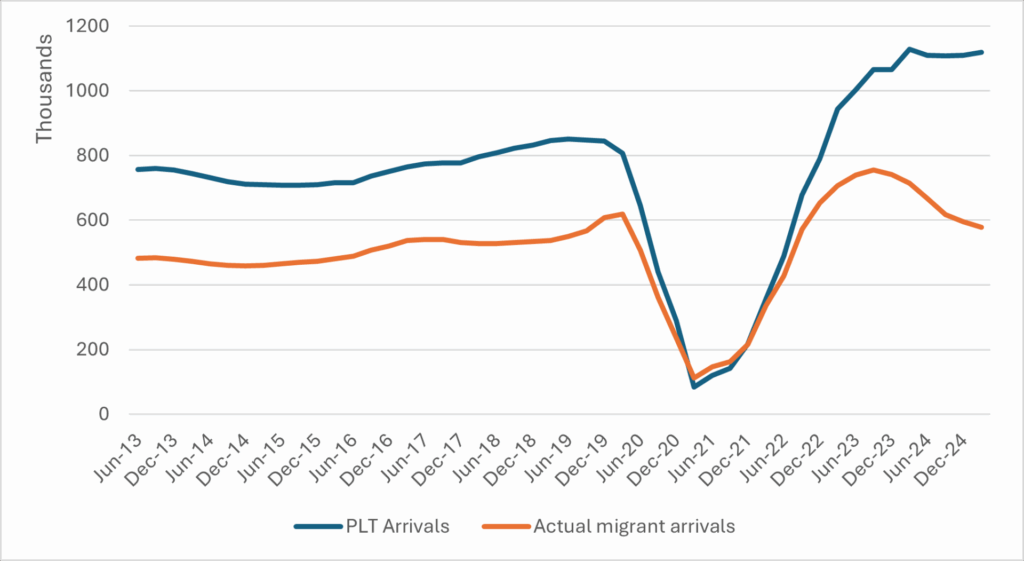

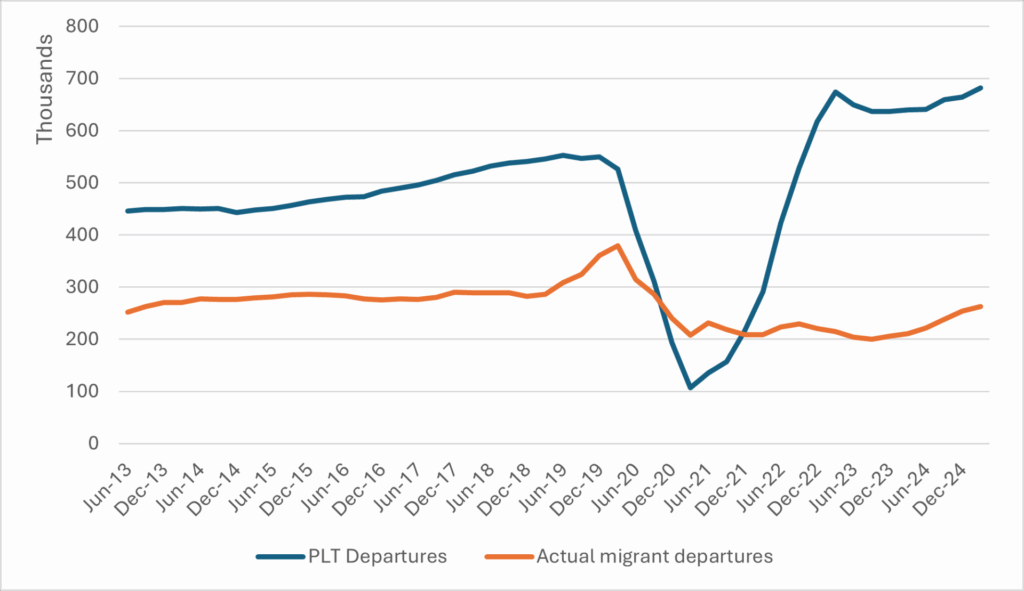

Because they count different things, PLT and NOM diverge substantially. Over recent years PLT arrivals have averaged about 23–30% higher than actual migrant arrivals (Figure 1). And PLT departures have been 115–135% higher than true migrant departures.

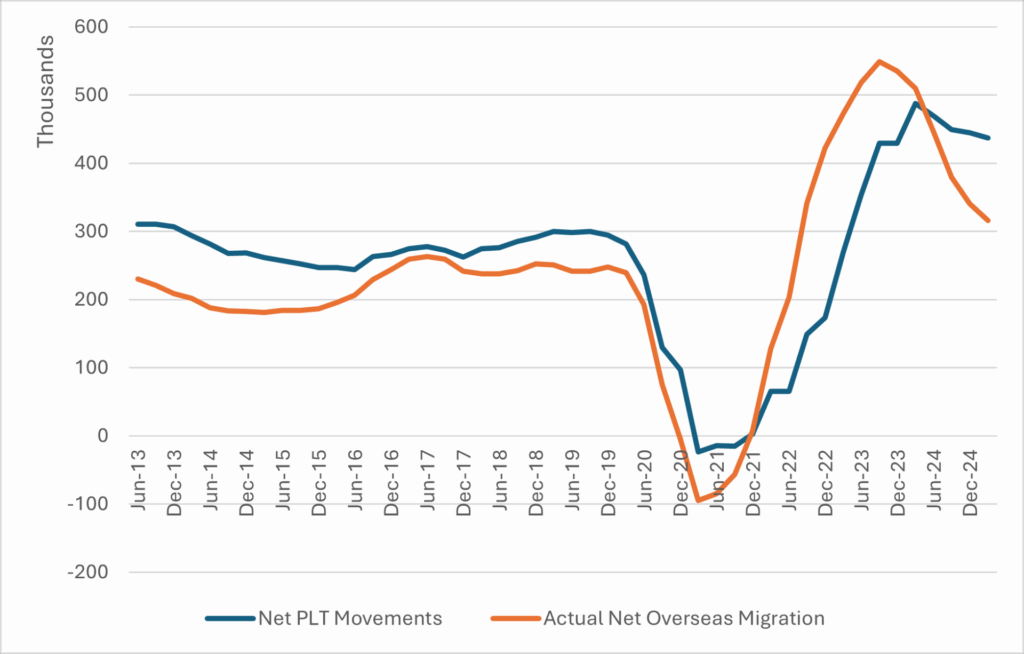

Under volatile conditions (like the post-COVID border reopening), these differences explode. For example: the gap between ‘Net PLT’ and NOM currently exceeds 120,000 people – a margin nearly two-thirds as large as Australia’s permanent migration program.

When numbers align by chance, that can give a false confidence, but when conditions shift the errors become massive. Experts call this ‘correlated measurement error’. In layperson’s terms, mixing PLT with migration is a recipe for incorrect conclusions.

Why is this such a big deal?

When PLT is treated as if it measures migration, it distorts public understanding. Arrivals and departures appear inflated, encouraging sensational headlines and misleading charts that undermine trust in evidence.

Figure 3 is a case in point. Currently Net Overseas Migration is plummeting, and it has been for some time, as shown by the orange line. But many Australians falsely believe that the opposite is happening, because they have been shown the blue line. They are being misled by rogue commentators misusing the PLT data.

The consequences extend to policy and planning. Decisions about housing, infrastructure, labour markets and public services rely on migration as defined by NOM. Substituting PLT weakens policy responses and leads to poor allocation of resources.

There are also risks for social cohesion. Misinterpreted data can fuel fear-based narratives, and we have seen PLT figures used by extremist groups to support neo-Nazi rallies. Clear, accurate data is essential for a well-informed and inclusive society.

Finally, research integrity is at stake. The ABS explicitly warns that PLT “should not be used to measure migration.” Overlooking that guidance – especially in public communication – can amount to research misconduct when intent or impact is significant.

As the Australian Statistician has stated in relation to this matter, reliable data is a pillar of informed debate and good policy making.

I’m a journalist or politician, what should I do?

In the public debate on migration, we shouldn’t be talking about Net Permanent and Long-Term movement at all. That’s travel data – it measures trips, not migration – and if someone tells you differently, there’s a good chance they are engaged in research misconduct, which is a serious offence at any serious research institution.

If you’re a journalist or politician, the most important step is to use NOM when discussing migration-driven population change. It is the internationally accepted standard and the measure built into Australia’s legal and institutional frameworks.

PLT data measures travel behaviour. It measures a totally different concept from migration. Confusing them doesn’t just produce technical errors – it misleads debates, undoes policy foundations and fuels divisions.

If Australia wants an informed, grounded debate about migration – one that builds trust and supports good policy – we must insist on the correct measure. That means using NOM, every time.

So, tell us, is migration going up, or down – and who should I believe?

The answers are simple: Net Overseas Migration is going down fast. And you should not believe anyone who is using bogus travel and tourism data to tell you differently.