Love on hold: fixing Australia’s broken Partner visa system

Why are tens of thousands of Australian citizens being forced to wait years – and pay thousands – just to live with their partners? The ANU Migration Hub’s Peter McDonald and Alan Gamlen explain how to fix Australia’s unlawful Partner visa crisis.

Read time: 9 mins

By Emeritus Professor Peter McDonald and Professor Alan Gamlen of the ANU Migration Hub. The Migration Hub works to support evidence-based migration policy through research and collaboration. To learn more or support the Hub’s efforts, contact migrationhub@anu.edu.au.

“‘Illegal’ is a pretty strong word to throw at a minister, but it’s true. Under the Migration Act, the minister has the power to cap and queue the number of visas issued each year for most visa classes. But spouse, partner and dependent child visas are different. Section 87 of the act explicitly states that the minister cannot cap those visas. They’re supposed to be demand-driven, acknowledging the reasonable right of Australians to fall in love and build a life with their partner here. The Hawke and Howard governments tried to pass legislation to give the minister the power to cap these visas, but both times this was rejected by the Senate. The government know that what they’re doing is not just cruel; it is illegal.”

– Hon Julian Hill MP, Speech to the House of Representatives, 31 August 2020

What’s the problem with Partner visa processing in Australia?

When the Hon Julian Hill MP made this stirring statement to Australia’s Parliament, he was an opposition backbencher. As he noted, the Parliament has twice affirmed that grants of permanent residence visas to partners of Australian citizens should be ‘demand-driven’ – that is, the number of grants should move up and down based on the number of applications.

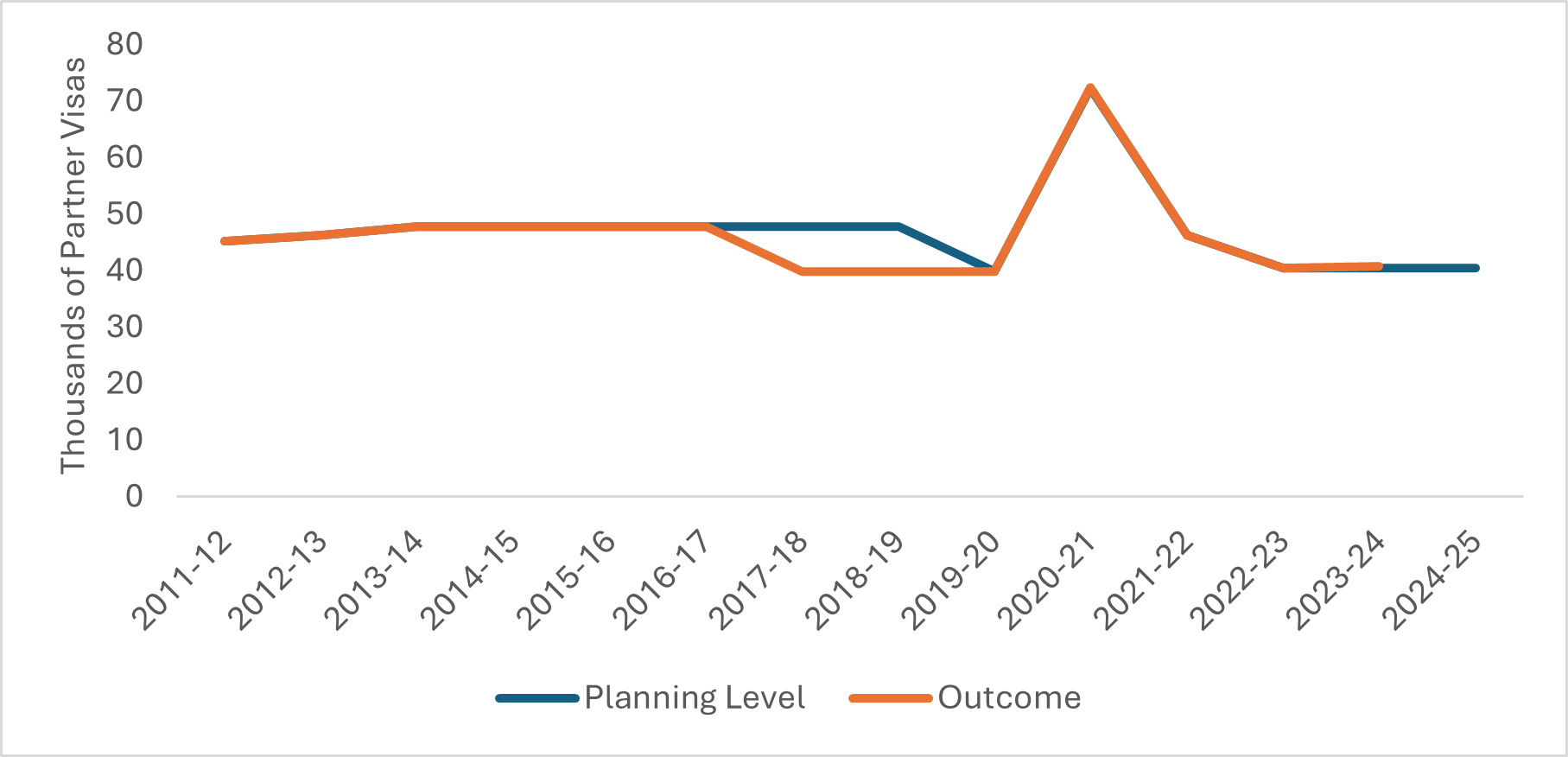

Figure 1: Demand-driven, by law — but capped in practice

To support his claim that visas had been capped, Mr Hill showed evidence that the annual number of Partner visas granted closely matched the limit set in the government’s annual permanent migration plan (see Figure 1).

He claimed this demonstrated the government was using this ‘administrative mechanism’ to unlawfully cap Partner visas, in spite of Section 87 of the Migration Act. This practice, he noted, had begun in the final years of the Howard government and had been replicated by every subsequent government.

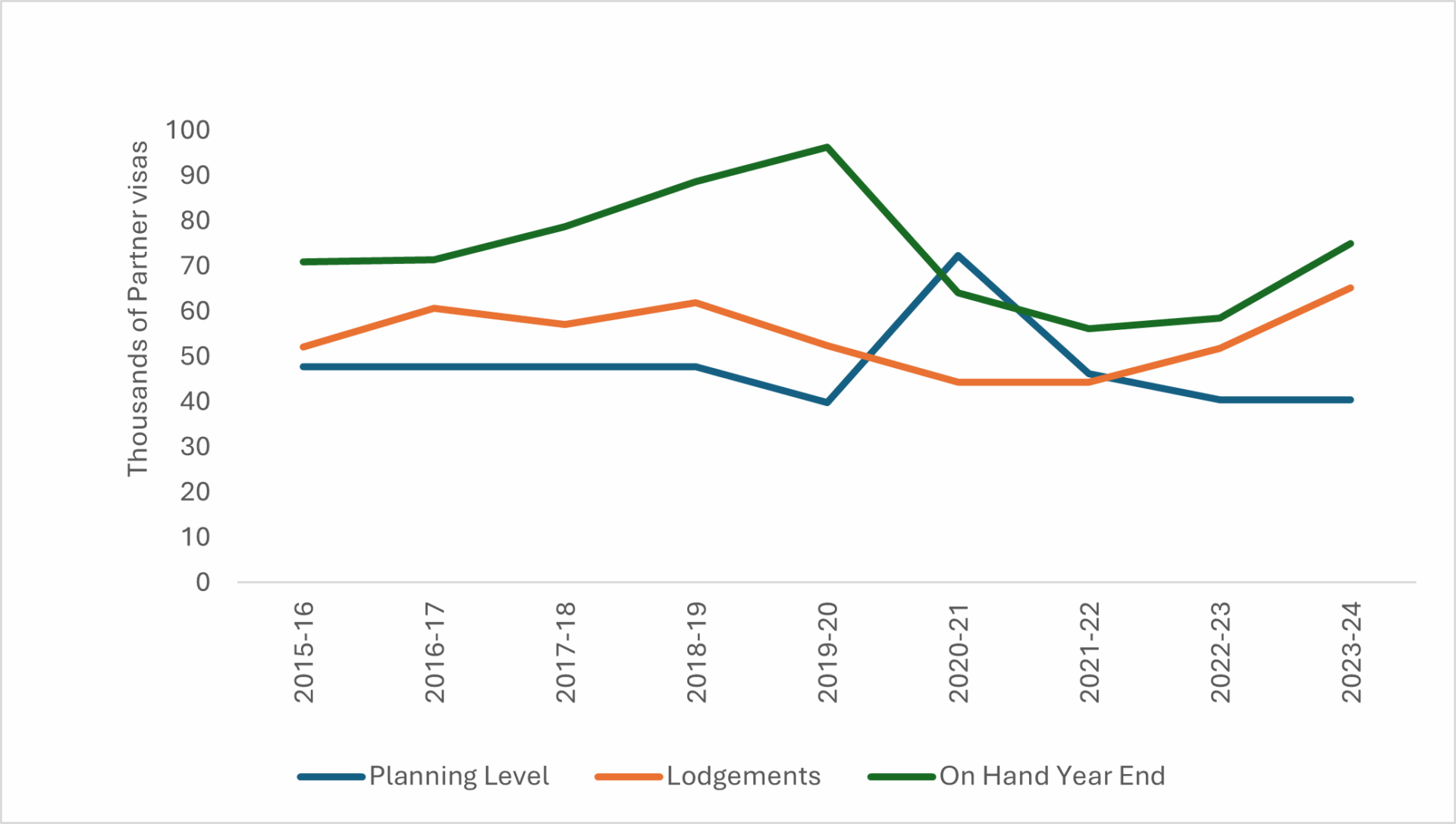

Mr Hill also observed that the then-Coalition government had “collected massive levels of visa application revenue that should be used to process applications in a timely way,” but that processing times had blown out to more than two years in many cases. He noted that, at the end of March 2020, there were 91,717 visa applications waiting to be actioned. He described it as an “extraordinary blowout”.

In the 2020 debate, Mr Hill was supported by Labor’s Andrew Giles and independent MP Helen Haines. Mr Hill’s views were opposed by Liberal members Julian Lesser, Tim Wilson and Julian Simmons, who all supported the then-government’s approach to the issue.

What’s the situation now after three years of Labor government?

Today, the number of applications on hand is sitting at around 100,000 (see Figure 2). And as Figure 1 shows, the number of grants each year has been nearly exactly the same as the level set in advance in the permanent migration planning levels. Based on present indicators, this situation will continue in 2025-26.

Figure 2: The growing problem of Partner visa processing

In other words, there has been no change.

Mr Hill is now Australia’s Assistant Minister for Citizenship, Customs and Multicultural Affairs. If the Coalition was breaking the law in 2020, as Mr Hill claimed, then Labor has followed suit. People currently awaiting an outcome have paid almost $1 billion in application fees to the government without receiving the result they are entitled to under Section 87.

The problem with Partner visa processing in Australia is, unfortunately, now even worse than when Mr Hill addressed Parliament in 2020.

So far, no action has been taken despite the following recommendation made by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit in November 2024:

The Committee recommends that the Australian Government consider further reforms to make the partner and child family visa programs truly demand-driven with reasonable waiting times, excising these streams from the annual headline permanent migration cap and allocating sufficient processing resources annually to meet projected demand with a reasonable average processing time (JCPAA 2024).

Why have successive governments behaved in this way?

The total annual Permanent Migration Program Planning Level covers both the Skill stream and the Family stream (which consists mainly of partners of Australian citizens). For the past 15 years, this level has been set at a near-constant 190,000.

If the government of the day was to respond to the increasing demand for Partner visas in the Family stream, it would have to reduce the number of visas granted in the Skill stream in order to maintain the capped total Permanent Migration Program Planning Level.

This is politically difficult because the Australian economy depends on skilled migration. This places the government of the day in a catch-22 situation.

But the solution is very simple: take the grants to partners of Australian citizens out of the annual planning program and allow the Partner visa grants to respond to demand. This separation approach was used by the Coalition government in 2013.

No planning level was set for children – in fact, the child category was taken out of the total program. Consequently, the number of grants to children fluctuated in response to demand.

This category separation for children stayed in place until 2022-23 when, inexplicably, the new Labor government put the child category back into the total program and made it subject to an annual planning level. We say inexplicably because the number of grants to children is very small.

Children of Australian citizens are eligible to become citizens themselves. Minors that may require permanent residence include those adopted by Australian citizens and those who are children of New Zealand citizens and Australian permanent residents.

As migration experts, we support the position put forward by Mr Hill five years ago and the recommendation made by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

In fact, the position that Mr Hill took in the debate is one we argued in a policy paper prepared for the Department of Immigration and Citizenship more than a decade ago (McDonald 2013).

The issue with Partner visas is not the assistant minister’s fault – in fact, he has done more than most to address it.

And we trust that he is continuing to advocate for change along the lines of the recommendation made last year by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

Previous governments may have prioritised other political pressures on immigration, but Labor’s decisive 2025 re-election weakens that excuse.

Beyond a general reluctance to stir up immigration debates, there’s little reason not to act on the Partner visa problem.

What are the consequences of capping visas for partners of Australian citizens?

In his 2020 address to the House of Representatives, Mr Hill stressed the personal and emotional consequences: “relationships are now stressed or broken as waiting times continue to increase”.

Mr Hill also noted that couples were unable to plan their lives such as having children or buying a house.

Beyond these important repercussions, if a potentially skilled Australian citizen has a partner living outside of Australia, there is a good chance they could leave the country themselves and fail to return.

As indicated by the following table, capping of Partner visas also constitutes discrimination against Australian citizens in comparison with the partners of new skilled migrants.

There is also a degree of gender discrimination, as partners of Australian citizens are more likely to be female than the partners of new skilled migrants.

It is our understanding that delays in the issuance of partner visas is one of the leading complaints on the desks of members of the Federal Parliament. Reform would bring this situation to an end.

Table 1. Comparing treatment of different Partner visa categories in Australia

| Partner of Australian Citizen

(primary applicants) * |

Partner of New Skilled Migrant (secondary applicants aged 20 and over) | |

| Number of grants in 2023-24

|

33,627 | 37,751 |

| % resident in Australia at grant

|

64.5% | 61.9% |

| % Female

|

68.0% | 55.9% |

| Application fee

|

$9,365 | $2,445 |

| Waiting time | Varies, 15-25 months, shorter if resident in Australia | Immediately upon grant to partner |

| Nature of grant | Provisional for two years | Immediate permanent residence |

| Genuine relationship test

|

Stringent | Much less stringent |

| Limitation of grants | Limit set by the annual migration planning levels | No limit |

| Education fees | Must pay international student fees | Domestic student fees |

| Pipeline (applications on hand) | Around 100,000 and growing fast | No pipeline when partner has permanent residence |

*Also includes partners of eligible New Zealand citizens and Australian permanent residents.

Demand for Partner visas will continue to increase, meaning that the number of applications on hand will continue to grow, for multiple reasons.

Demand is growing partly because of the large numbers of young Australians meeting overseas partners. Many Partner visa applicants have resided in Australia on a student, graduate or working holiday visa. Others have met single young Australians who are travelling the world.

It is not just impossible to limit such partners from applying for a Partner visa – it is largely impossible to prevent them from entering the country and remaining here for an extended period.

Partners of Australian citizens can enter the country on a visitor visa, then apply for a Partner visa once here, and then remain here on a Bridging visa until their case is decided.

Therefore, this issue will not go away unless the solution that we suggest is adopted.

What would solve the government’s problem with Partner visa processing?

It’s very simple: take the grants for partners of Australian citizens out of the annual planning program and allow the partner grants to respond to demand.

Under our proposal, three categories of visa could be separately capped: principal applicants in the Skill stream, parents in the Family stream, and humanitarian migrants.

Partners and children in the current Family stream would be uncapped and secondary applicants in the Skill stream would be uncapped (as they are at present).

A consequence of following this advice would be that the number of people granted permanent residence in a year would rise.

However, the increase would only be marginal, because almost two thirds of the applicants are already in Australia on temporary visas and do not add to net overseas migration or housing demand. If they are already in Australia, all that happens is that their visa becomes permanent sooner than it would have otherwise.

This approach directly addresses a key issue identified in the 2024 review of Australia’s Migration System: the system’s failure to support long-term settlement and the need to “restore permanent residence to the heart of our migration system”.

The government’s strategic response to the review pledged to “build stronger Australian communities” by planning migration better and enabling permanent residence and citizenship. Our proposal aligns with this commitment to “end settings that drive long-term temporary stays”.

Another advantage of this approach is that greater attention could be focussed upon the issuance of visas in the Skill stream. The Family stream is based on the legal rights of all Australians to a family life, whereas the Skill stream is based on the economic benefits of skilled migration.

Keeping these two streams separate would prevent conflicts between these different rationales, while enabling the government to gain more precise and transparent control of the capped categories.

A final advantage of our approach is that the government will avoid the legality of what it is doing being tested in court. Under our proposal, Partner, Child, and other visa categories would be demand-driven, as the law requires, and the complaints to MPs would stop.