Migration is falling fast – but election politics is spinning a different story

Migration numbers are being weaponised during this election campaign to elicit panic and sway voters. But what does the trajectory of migration in Australia actually look like?

Read time: 6 mins

By Emeritus Professor Peter McDonald and Professor Alan Gamlen of the ANU Migration Hub. The Migration Hub works to support evidence-based migration policy through research and collaboration. To learn more or support the Hub’s efforts, contact migrationhub@anu.edu.au.

The coming election campaign is likely to be marked by induced panic over migration numbers.

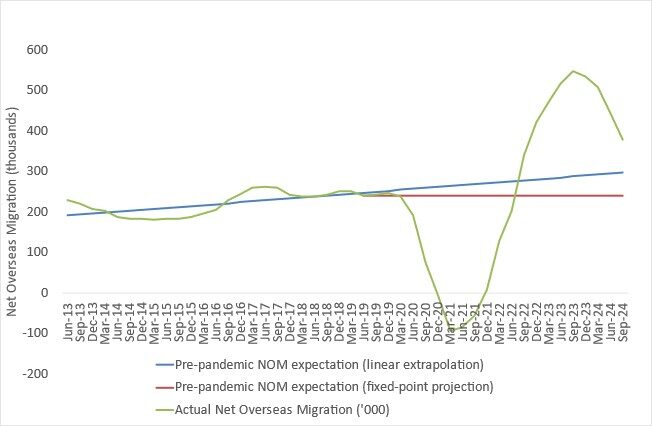

Between mid-2022 and mid-2024, net overseas migration (NOM) rose to unprecedented levels, reaching a peak of 535,000. However, migration is already falling faster than it rose during the surge (Figure 1).

In the recent budget, Treasury has estimated that the number will fall to 340,000 in the 2024-25 financial year, and keep falling to 260,000 the following year. By 2027, migration levels in Australia could plummet to historic lows.

Despite this, claims of out-of-control migration continue to grab headlines. Narratives around migration numbers negatively affecting housing supply and affordability have contributed to the inaccurate perceptions many Australians have been found to have about migrants and migration.

So, even though net overseas migration is falling by 100,000 per annum, during the election campaign we may be led to believe that the very high levels of migration between mid-2022 and mid-2024 will continue because of alleged mismanagement at the hands of the current Labor government. It is important to cut through this noise and focus on the bigger picture of migration in Australia.

Here is how the high levels of net overseas migration have occurred, why they are now falling and how migration could plummet in the future.

Figure 1: Net Overseas Migration, compared to pre-pandemic expectations

Why has net migration been so volatile recently?

Net overseas migration is just arrivals minus departures. The sudden surge and subsequent decline in migration numbers is due to changes in both these factors.

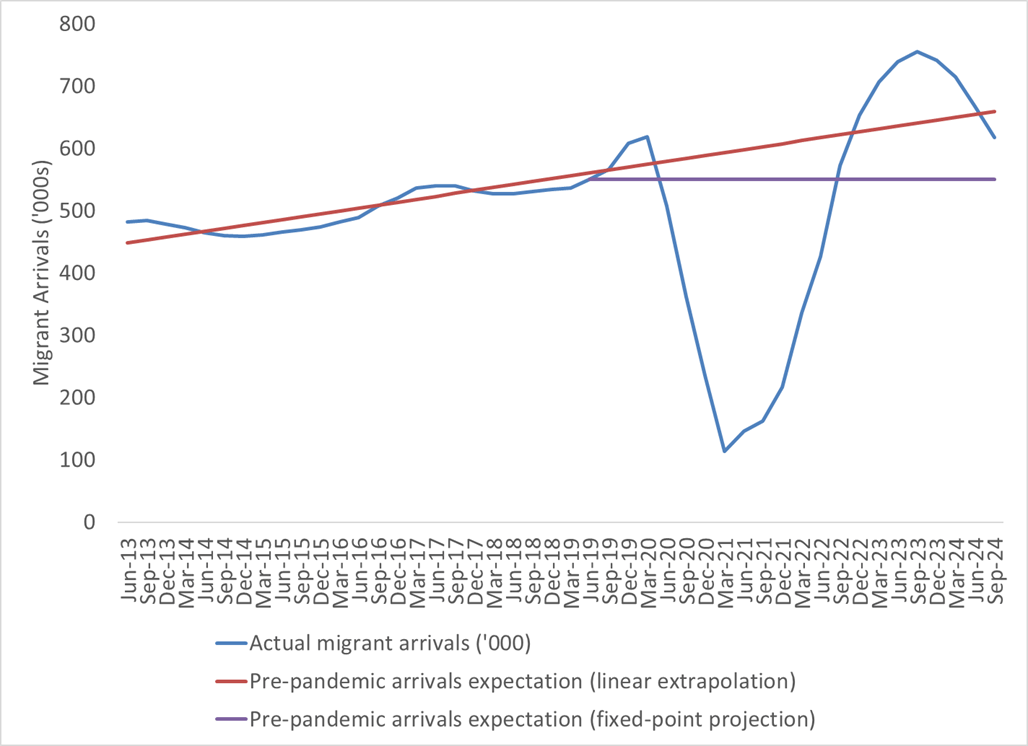

First, arrivals recovered from COVID-19 (Figure 2). Because the country’s border was closed during the pandemic, there was a two to three-year build-up of demand for temporary visas, particularly International Student visas and the Working Holiday Maker program.

In the case of Working Holiday Makers, there was a double demand boost: new agreements allow backpackers from the United Kingdom and Ireland to stay for up to three years.

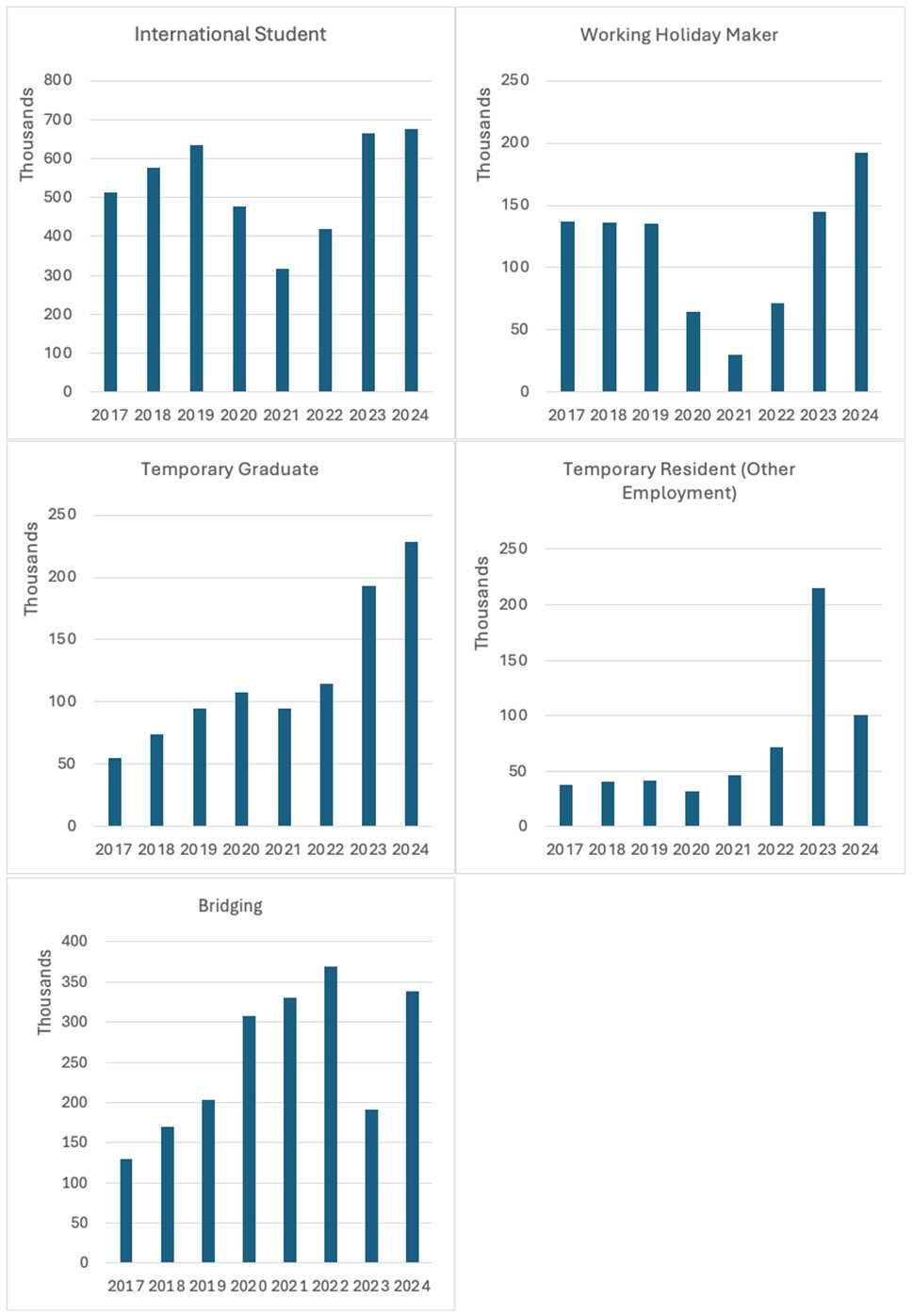

Both visa types grew significantly from September 2022 to September 2024 (as shown in Figure 4 below).

Meanwhile, the number of International Students has returned to pre-pandemic levels while Working Holiday Makers have increased to a record high.

Figure 2: Migrant arrivals, compared to pre-pandemic expectations

As Figure 2 shows, the pandemic-era shortfall of arrivals was actually much larger than the recovery that has occurred since.

The pent-up demand has now largely been met, and the federal government has moved to restrict the number of migrants arriving on a student visa. Working Holiday Maker arrivals are likely to cease rising as the pent-up demand ebbs further.

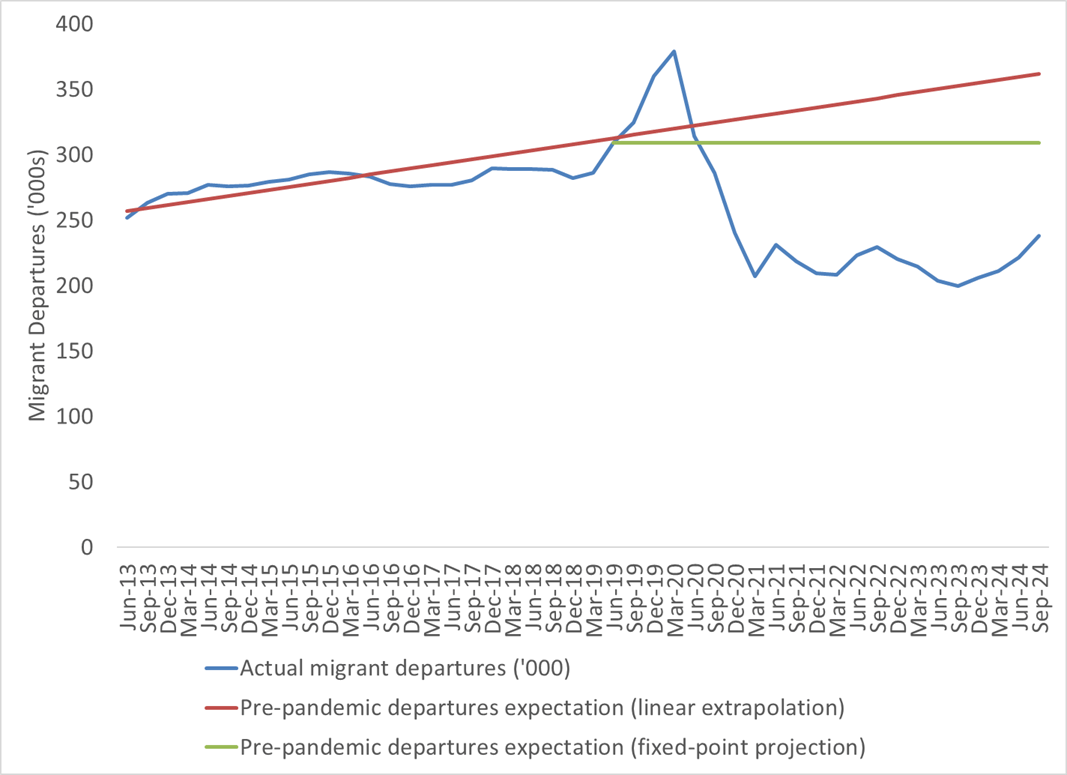

However, the arrivals trend isn’t the main factor influencing net overseas migration. The second, and larger, reason for the extraordinary recent net overseas migration fluctuations is departures (Figure 3). Like arrivals, departures took a nosedive during the pandemic. Unlike arrivals, departures haven’t yet recovered.

Why are departures still so low?

This massive cumulative shortfall in departures is due to a combination of:

- Long-term visa processing delays and backlogs.

- Visa extensions and exceptions during the pandemic, which haven’t expired yet.

- ‘Visa hopping’, where migrants switch from one type of temporary visa to another.

Figure 3: Migrant departures, compared to pre-pandemic expectations

Under the previous Coalition government, the number of migrants on Bridging visas rose substantially year on year from 2013, mainly because of long-term visa processing delays and backlogs (Figure 4). The new Labor government hired more workers to clear the backlog, and this explains the fall in numbers on the Bridging visa between 2022 and 2023.

However, the number of migrants on the Bridging visa rose sharply from September 2023 to September 2024 partly because this visa has become the ‘last resort’ for those wishing to extend their stay in Australia.

For example, migrants whose last resort has expired but they have not yet left the country. In January 2025, there were 92,000 individuals that were not granted a final Protection Visa and were yet to be deported.

As an example of visa extensions during the pandemic, the Coalition government extended eligibility for the Temporary Resident (Other Employment) visa during the pandemic, to enable people to work who had difficulty leaving Australia because of closed borders. More than 200,000 people took up the opportunity in one year.

Similarly, at the tail end of the pandemic disruption, the current Labor government extended the duration of the Temporary Graduate visa from two to four years. A very large number of former students exercised this option (see Figure 4).

Along with other policy changes, like the previously mentioned one for backpackers from the United Kingdom and Ireland, these pandemic-era measures have led to the emergence of a very large number of temporary migrants currently holding visas of the longer three to four years duration.

Figure 4: Temporary visa holders present in Australia, by visa type, 30 September of each year

What will happen to this bulge of potential departures in the coming years? Some will extend their stay in Australia by ‘visa hopping’ – that is, switching from one type of temporary visa to another.

For example, the Temporary Resident (Other Employment) is a two-year visa, and as Figure 4 shows, the numbers in this category are already falling sharply. But some holders of the Temporary Resident (Other Employment) visa may have hopped onto a Bridging visa.

Similarly, many international students will complete their study and move onto the Graduate visa, adding to the cohort already on that visa with two to three years’ time remaining. The number of migrants on the Graduate visa will be curtailed in the future as the government has cut the duration of the visa back to two years.

But a high proportion of graduates can be expected to apply for permanent residence, which means they will hop onto a Bridging visa. The duration of this visa will depend upon the speed of processing, and some will be granted permanent residence.

Where is net overseas migration headed in the future?

Not all temporary migrants will move onto a different visa when their current one expires. Many will also depart as their visas and extensions expire, as backlogs clear, and as regulators limit visa hopping. In this way, the bulge of delayed departures will gradually diminish over time.

The departure numbers will be small in the next couple of years but they will increase sharply in three to four years’ time. If the next government is still controlling arrivals by then, net overseas migration could fall sharply.

In summary, despite overseas migration reaching unprecedented levels in the 2022-23 financial year, net overseas migration to Australia has fallen by 100,000 in each of the past two years, and it can be expected to continue falling at a moderate rate in the next two years.

However, from about 2027, as the number of departures expands considerably, net overseas migration is likely to plummet.

This does not seem like a situation that should give rise to election-generated panic about high migration levels. In fact, the bigger risk is that undue panic could induce knee-jerk migration cuts that cause migration levels to whipsaw up and down, instead of settling back into a more stable normal.