The big gender pay gap reveal exposes the good, bad and ugly of large Australian companies

Of Australia’s 20 top performing companies, 16 are underperforming on closing the gender pay gap. This is a worrying sign for gender equity in Australia, but public disclosure policies can incentivise companies to do better, Sally Curtis, Jananie William, and Anna von Reibnitz write.

Read time: 8 mins

Partly based on Gender pay gap reporting in Australia: Time for an upgrade, published October 2021.

This month marked the first public release of gender pay gaps for almost 5,000 private organisations by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) under new legislation passed in 2023. The numbers should come as no surprise to most reporting organisations – they have known their gender pay gaps for more than 10 years (under previous legislation) and their lack of accountability to reduce these gaps was a major motivator for the legislative changes that allowed this public release. It is important to recognise that the gender pay gap statistic is not all encompassing – for example, it doesn’t give any information about the gender composition in the organisation or hours worked. However, it does give a proxy on how an organisation is tracking with respect to workplace gender equality.

What does the data show?

According to the latest WGEA data, the total remuneration gender pay gap for Australia is now 19 per cent. This means the median pay for a woman in WGEA’s dataset is 19 per cent less than the median pay for a man. The median pay is the mid-point (or middle figure) if you line up pay in order of lowest to highest and is calculated for each gender. The median is used instead of the average to avoid any anomalies of particularly high or low salaries from skewing the figure. While such aggregated statistics provide an important gauge for monitoring progress, they tell us little about the distribution of pay gaps across organisations.

From this month, Australia can delve deeper than headline figures and we spotlight the gender pay gaps of Australia’s largest publicly listed companies by market capitalisation. Large companies often set the standard for other organisations and hold significant power to drive change. Generally speaking, large employers have smaller gaps, so we expected Australia’s top 20 companies to be leading the way. Unfortunately, the data tells a different story.

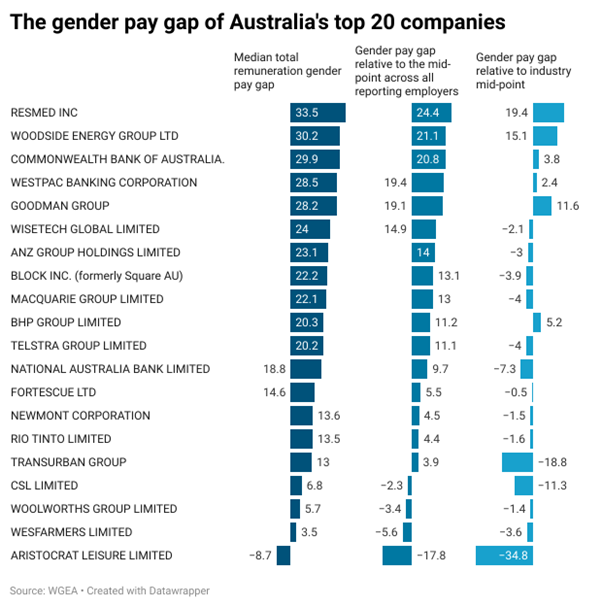

First, the bad news. The following chart shows the gender pay gaps of the top 20 publicly listed companies on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) measured by median total remuneration. 19 out of the top 20 companies have a gender pay gap that favours men. 16 underperform compared to the mid-point of all reporting employers (9.1 per cent) and six of these (Resmed, Woodside, Goodman Group, BHP, Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) and Westpac) underperform the mid-point of their industry counterparts. 11 of the top companies have a pay gap of more than 20 per cent.

Now to what can only be described as the ugly. Employers had the option of preparing a statement for publication on the WGEA website that provides context to their gender pay gap and their action plan for achieving progress. At the time of writing, only 13 of these companies provided a statement or link to their website, one company provided a link to a website with an error message, and six companies have not yet provided a statement. The silence from such large companies with large gender pay gaps is deafening.

Of the top 20 companies, there is one good news story, at least when it comes to workplace gender equality. Despite making large profits from the controversial gambling industry, Aristocrat, a gaming and technology company has a gender pay gap that favours women. According to the Aristocrat WGEA submission, the company has set targets to increase the representation of women, has a pay equity strategy in place and reports pay equity metrics to the executive.

In summary, these results show that the largest companies still have a lot of work to do. Australia’s gender pay gap transparency reforms might be the push that’s needed to enable this organisational change.

So, what now?

Emerging international research shows that increased transparency of wage differentials between men and women can lead to reductions in gender pay gaps. However, this research shows the mechanism through which this occurs is complex and varies by country. Governments adopting a public disclosure policy as the primary accountability mechanism are effectively relying on ‘market forces’ to reduce the gender pay gap. In other words, instead of implementing a reporting system whereby the government mandates corrective action or imposes penalties for not closing gender pay gaps, they rely on organisations and individuals in the market to push for progress.

This gives a wide range of stakeholders the ability to hold organisations to account. For example, employees could use gender pay gap data to exert pressure on their employer to address gender inequality. Job seekers could use the data to make decisions about where they work. Consumers could use gender pay gap data to inform purchasing decisions. In our 2021 study, we found evidence of investor interest in using gender pay gap information to screen organisations as part of their socially responsible investment strategies. These are all examples of market forces at work.

There is evidence that indicates that the threat of reputational damage acts as a powerful motive for genuine organisational change. There is more likely to be an effect on an organisation’s reputation when information about the organisation is highly publicised. The advantage of Australia’s system in this regard (which differs from other countries) is that the data is released by WGEA on the same day for all organisations. This suggests an important role for stakeholders such as the media, financial analysts, gender advocates, trade unions, and academics to leverage this release and disseminate information about gender pay gaps to increase awareness in the market. Industry and peak bodies can also use their respective knowledge and platforms to disseminate information and support member organisations to make meaningful changes.

So, while it remains to be seen how the market will react to the first release of employer gender pay gap data in Australia, there are a wide range of stakeholders that are now empowered to take a more active role in driving change. Furthermore, given the emerging evidence from other countries, it is also clear that monitoring the mechanisms of organisational change is important to ensure the changes will be beneficial for all women regardless of the industry they work in, the role they perform or their level of seniority within the organisation. Finally, the responsibility to address workplace gender equality ultimately still sits with employers – but now they have many more stakeholders watching.