Read time: 6 mins

Based on More for Children Issues Paper: Food Insecurity, by Cadhla O’Sullivan, Sharon Bessell, and Megan Lang, published October 2024.

According to ANU child poverty research, many Australian children live in ‘food deserts’: low-income, regional and outer suburban communities where food is chronically undersupplied. In some families, the cost-of-living crisis is so severe that children are acutely aware of food prices and taking it on themselves to help. Their stories highlight the urgent need for policies that mitigate the shortcomings of a price-led food supply chain.

Read time: 6 mins

Based on More for Children Issues Paper: Food Insecurity, by Cadhla O’Sullivan, Sharon Bessell, and Megan Lang, published October 2024.

1

Children as young as six are acutely aware of Australia’s cost-of-living crisis but for many, the crisis is not new and is characterised by hunger, according to the ANU experts behind the More for Children project.

2

While school-provided meals and food charities help, many children describe living in ‘food deserts’ where market failures have made high-quality food artificially scarce.

3

The evidence indicates that policies targeting artificial food scarcity would help children in poverty. Actions need to include just systems of food distribution, addressing both food deserts and monopolies in some communities, and addressing poor residential planning.

When asked what makes life good, Australian children talk about food.

Thankfully, these children live in one of the most food secure countries in the world. In 2020, the Department of Agriculture produced a report on Australia’s food security in response to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, concluding that ‘food security is not a problem for Australia.’

The report also noted that Australia produces more food than it consumes, and that agricultural exports act as a ‘shock absorber’, keeping domestic food supply stable.

Yet since then, the price of food has risen more than 17 per cent for working households, triggering multiple public inquiries into the operation of Australian supermarkets. For families struggling with poverty, unaffordable food is not new.

Speaking to ANU experts about their experiences of poverty for the More for Children project, children described life in Australia’s ‘food deserts’, where nutritious, affordable food isn’t available to communities.

Children interviewed for the project, some as young as six years old, were strikingly aware of the cost-of-living crisis. Speaking to ANU researchers – who used a rights-based, child-centred methodology to learn about the children’s lives – they were able to identify which kinds of food their family could afford, and the cost of these items.

One 12-year-old boy, whose research nickname is ‘Barry’,* said, “Yeah, it’s hard ’cause we have like so many people in our family, an average grocery shop in our family is like 400 dollars every week to two weeks. One time it was like 800 dollars”

Many children had independent tactics for coping with high food prices. For instance, one 14-year-old girl told researchers she had used social media platforms to find cheaper recipes for her family.

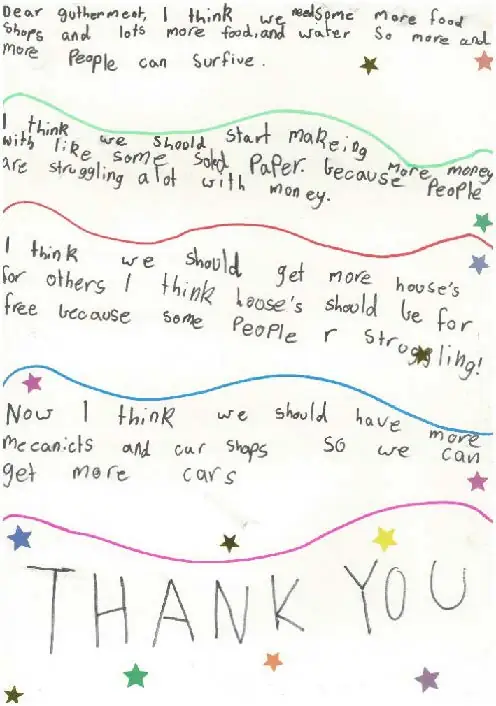

“I think we need some more food shops and lots more food, and water so more and more people can surfive [sic].”

One 12-year-old boy told researchers he often missed school when the family didn’t have enough food for lunches. He was so attuned to high prices that he mentioned the influence of war in Ukraine.

“Stop the war in Ukraine to lower the food prices ‘cause the food prices are going up.” ‘X’ said.

Some children are able to get help, accessing school-provided meals and food charities.

“They take those [food packages] to people who have struggles getting food, and it’s a big help…and sometimes they let us take some of the food home when my mum doesn’t have enough money to pay the Woolies” (‘Apple’, eight years old).

But the occasional free bowl of cereal can only do so much. And not all schools can afford to offer meals.

“[At school] we get free breakfast, if you want breakfast … I think we need more schools out here like that so that every child has access to this, so mums and dads don’t have to spend even more money buying lunch, tea, snacks and their money is just decreasing, decreasing and decreasing and prices are just going up and up and up so their money is just getting tighter and they’re not going to be healthy (‘Slim Shady’, 11 years old).

When they don’t have a lunch to bring to school, many children skip the day’s learning entirely, rather than face the anxiety of going without food.

The experts, from the ANU Children’s Policy Centre at Crawford School of Public Policy, said that to ease immediate cost-of-living pressures on Australian children, argue that better resourcing of food charities and the provision of school meals are essential in responding to urgent need, but systemic reform of the food system and its underlying incentives is needed.

In the researchers’ own words, “food deserts are real”, and until public policies recognise and combat artificial scarcity, they will continue perpetuating and exacerbating poverty.

*All quotes attributable to children are under their chosen nicknames

"Food deserts are real. Until public policies recognise and combat artificial scarcity, they will continue perpetuating and exacerbating poverty."